Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Monday, June 8, 2009

Rising Above I.Q by Nicholas D. Kristof

In the mosaic of America, three groups that have been unusually successful are Asian-Americans, Jews and West Indian blacks — and in that there may be some lessons for the rest of us.

Asian-Americans are renowned — or notorious — for ruining grade curves in schools across the land, and as a result they constitute about 20 percent of students at Harvard College.

As for Jews, they have received about one-third of all Nobel Prizes in science received by Americans. One survey found that a quarter of Jewish adults in the United States have earned a graduate degree, compared with 6 percent of the population as a whole.

West Indian blacks, those like Colin Powell whose roots are in the Caribbean, are one-third more likely to graduate from college than African-Americans as a whole, and their median household income is almost one-third higher.

These three groups may help debunk the myth of success as a simple product of intrinsic intellect, for they represent three different races and histories. In the debate over nature and nurture, they suggest the importance of improved nurture — which, from a public policy perspective, means a focus on education. Their success may also offer some lessons for you, me, our children — and for the broader effort to chip away at poverty in this country.

Richard Nisbett cites each of these groups in his superb recent book, “Intelligence and How to Get It.” Dr. Nisbett, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, argues that what we think of as intelligence is quite malleable and owes little or nothing to genetics.

“I think the evidence is very good that there is no genetic contribution to the black-white difference on I.Q.,” he said, adding that there also seems to be no genetic difference in intelligence between whites and Asians. As for Jews, some not-very-rigorous studies have found modestly above-average I.Q. for Ashkenazi Jews, though not for Sephardic Jews. Dr. Nisbett is somewhat skeptical, noting that these results emerge from samples that may not be representative.

In any case, he says, the evidence is overwhelming that what is distinctive about these three groups is not innate advantage but rather a tendency to get the most out of the firepower they have.

One large study followed a group of Chinese-Americans who initially did slightly worse on the verbal portion of I.Q. tests than other Americans and the same on math portions. But beginning in grade school, the Chinese outperformed their peers, apparently because they worked harder.

The Chinese-Americans were only half as likely as other children to repeat a grade in school, and by high school they were doing much better than European-Americans with the same I.Q.

As adults, 55 percent of the Chinese-American sample entered high-status occupations, compared with one-third of whites. To succeed in a profession or as managers, whites needed an average I.Q. of about 100, while Chinese-Americans needed an I.Q. of just 93. In short, Chinese-Americans managed to achieve more than whites who on paper had the same intellect.

A common thread among these three groups may be an emphasis on diligence or education, perhaps linked in part to an immigrant drive. Jews and Chinese have a particularly strong tradition of respect for scholarship, with Jews said to have achieved complete adult male literacy — the better to read the Talmud — some 1,700 years before any other group.

The parallel force in China was Confucianism and its reverence for education. You can still sometimes see in rural China the remains of a monument to a villager who triumphed in the imperial exams. In contrast, if an American town has someone who earns a Ph.D., the impulse is not to build a monument but to pass a hat.

Among West Indians, the crucial factors for success seem twofold: the classic diligence and hard work associated with immigrants, and intact families. The upshot is higher family incomes and fathers more involved in child-rearing.

What’s the policy lesson from these three success stories?

It’s that the most decisive weapons in the war on poverty aren’t transfer payments but education, education, education. For at-risk households, that starts with social workers making visits to encourage such basic practices as talking to children. One study found that a child of professionals (disproportionately white) has heard about 30 million words spoken by age 3; a black child raised on welfare has heard only 10 million words, leaving that child at a disadvantage in school.

The next step is intensive early childhood programs, followed by improved elementary and high schools, and programs to defray college costs.

Perhaps the larger lesson is a very empowering one: success depends less on intellectual endowment than on perseverance and drive. As Professor Nisbett puts it, “Intelligence and academic achievement are very much under people’s control.”

Asian-Americans are renowned — or notorious — for ruining grade curves in schools across the land, and as a result they constitute about 20 percent of students at Harvard College.

As for Jews, they have received about one-third of all Nobel Prizes in science received by Americans. One survey found that a quarter of Jewish adults in the United States have earned a graduate degree, compared with 6 percent of the population as a whole.

West Indian blacks, those like Colin Powell whose roots are in the Caribbean, are one-third more likely to graduate from college than African-Americans as a whole, and their median household income is almost one-third higher.

These three groups may help debunk the myth of success as a simple product of intrinsic intellect, for they represent three different races and histories. In the debate over nature and nurture, they suggest the importance of improved nurture — which, from a public policy perspective, means a focus on education. Their success may also offer some lessons for you, me, our children — and for the broader effort to chip away at poverty in this country.

Richard Nisbett cites each of these groups in his superb recent book, “Intelligence and How to Get It.” Dr. Nisbett, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, argues that what we think of as intelligence is quite malleable and owes little or nothing to genetics.

“I think the evidence is very good that there is no genetic contribution to the black-white difference on I.Q.,” he said, adding that there also seems to be no genetic difference in intelligence between whites and Asians. As for Jews, some not-very-rigorous studies have found modestly above-average I.Q. for Ashkenazi Jews, though not for Sephardic Jews. Dr. Nisbett is somewhat skeptical, noting that these results emerge from samples that may not be representative.

In any case, he says, the evidence is overwhelming that what is distinctive about these three groups is not innate advantage but rather a tendency to get the most out of the firepower they have.

One large study followed a group of Chinese-Americans who initially did slightly worse on the verbal portion of I.Q. tests than other Americans and the same on math portions. But beginning in grade school, the Chinese outperformed their peers, apparently because they worked harder.

The Chinese-Americans were only half as likely as other children to repeat a grade in school, and by high school they were doing much better than European-Americans with the same I.Q.

As adults, 55 percent of the Chinese-American sample entered high-status occupations, compared with one-third of whites. To succeed in a profession or as managers, whites needed an average I.Q. of about 100, while Chinese-Americans needed an I.Q. of just 93. In short, Chinese-Americans managed to achieve more than whites who on paper had the same intellect.

A common thread among these three groups may be an emphasis on diligence or education, perhaps linked in part to an immigrant drive. Jews and Chinese have a particularly strong tradition of respect for scholarship, with Jews said to have achieved complete adult male literacy — the better to read the Talmud — some 1,700 years before any other group.

The parallel force in China was Confucianism and its reverence for education. You can still sometimes see in rural China the remains of a monument to a villager who triumphed in the imperial exams. In contrast, if an American town has someone who earns a Ph.D., the impulse is not to build a monument but to pass a hat.

Among West Indians, the crucial factors for success seem twofold: the classic diligence and hard work associated with immigrants, and intact families. The upshot is higher family incomes and fathers more involved in child-rearing.

What’s the policy lesson from these three success stories?

It’s that the most decisive weapons in the war on poverty aren’t transfer payments but education, education, education. For at-risk households, that starts with social workers making visits to encourage such basic practices as talking to children. One study found that a child of professionals (disproportionately white) has heard about 30 million words spoken by age 3; a black child raised on welfare has heard only 10 million words, leaving that child at a disadvantage in school.

The next step is intensive early childhood programs, followed by improved elementary and high schools, and programs to defray college costs.

Perhaps the larger lesson is a very empowering one: success depends less on intellectual endowment than on perseverance and drive. As Professor Nisbett puts it, “Intelligence and academic achievement are very much under people’s control.”

Sunday, June 7, 2009

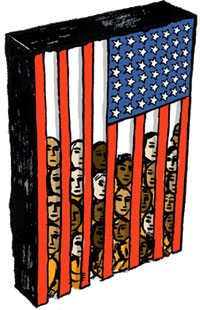

Cage Match by Dahlia Lithwick

The public-opinion two-step on the wisdom of closing the prison camp at Guantanamo is fascinating, and not just because Americans are now inclined to keep the detention facility there open forever. The current legal meltdown about what to do with prisoners still at Guantanamo shows that contrary to popular belief, Americans care a good deal about prisons, prisoners, and prison reform, but only when the inmates threaten to tumble out into their backyards.

But there's the rub: We already have a prison problem, and it's already in our backyards. That's what Sen. James Webb, D-Va., wants us to understand as he launches an ambitious new effort to reform U.S. prisons nationwide. It's not quite as dramatic as the prospect of Abu Zubaydah escaping from the Supermax prison in Colorado and rampaging through the Rockies, but the U.S. prison crisis gets worse every year, and nobody seems to mind. Webb has decided to try to reignite the subject of prison reform, because he's convinced that when it comes to the prison problem, Americans need only know how to count.

Here are the facts about America's prisons, according to Webb:

The United States, with 5 percent of the world's population, houses nearly 25 percent of the world's prisoners. As Webb has explained it, "Either we're the most evil people on earth, or we're doing something wrong." We incarcerate 756 inmates per 100,000 residents, nearly five times the world average. At this point, approximately one in every 31 adults in the United States is in prison, jail, or on supervised release. Local, state, and federal spending on corrections now amounts to about $70 billion per year and has increased 40 percent over the past 20 years.

Webb has no problem locking up the serious baddies. In fact, he wants to reform the justice system in part so that we can incapacitate the worst of the worst. But Webb wants us to recognize that warehousing the nation's mentally ill and drug addicts in crowded correctional facilities tends to create a mass of meaner, more violent, less employable people at the exits. And unlike Guantanamo, there are always going to be exits.

The Justice Department estimates that 16 percent of the adult inmates in American prisons—more than 350,000 of those incarcerated—suffer from mental illness; the percentage among juveniles is even higher. And 2007 Justice statistics showed that nearly 60 percent of the state prisoners serving time for a drug offense had no history of violence and four out of five drug arrests were for drug possession, not sales. Webb also reminds us that while drug use varies little by ethnic group in the United States, African-Americans—estimated at 14 percent of regular drug users—make up 56 percent of those in state prison for drug crimes. We know all of this. The question is how long we want to avoid dealing with it.

Why does the senator from one of the country's most rabid lock-'em-up states believe that with two wars raging, an economy collapsing, and America's Next Top Model beckoning seductively, Americans are truly ready to grapple with his new legislation—the National Criminal Justice Commission Act of 2009—which establishes a blue-ribbon commission to review the nation's entire prison system?

Fear-based policies only get you so far, and when it comes to drugs and prisons, it's time to start thinking about reality. Webb says he looks forward to the challenge of communicating the problem to Americans and working together to solve it. He suspects that if Americans actually have the reality-based conversation about our disastrous prison policies, we'll understand that the trends all move in very dangerous directions: We lock up more people for less violent crime at ever greater expense, ultimately breeding more dangerous criminals and ignoring the worst.

The Guantanamo problem we've finally started to grapple with in a pragmatic, rather than symbolic, way—it's a dangerous place with some dangerous people—is a mere speck in the eye of America's larger prison program. An AP story last week described a small Montana town that was more than willing to take all of the Guantanamo prisoners and incarcerate them because, ultimately, a jail is a jail and prisoners are prisoners. If we are so worried about locking up a few terrorists for life in maximum-security U.S. jails, shouldn't we be giving at least some thought to the folks already there? As Dennis Jett observed recently in the Miami Herald, "even if everyone at Guantánamo were transferred to a U.S. prison it would amount to an increase of less than one hundredth of one percent in the total number incarcerated in this country."

Compared with the powder keg of our domestic prison system, Guantanamo actually starts to look pretty benign. And if we are going to have a huge national panic attack about detaining dangerous individuals after 9/11, let's be honest that the dangers of a handful of Guantanamo prisoners "rejoining the battlefield" or escaping from maximum-security prisons is far more remote than the crisis now festering in our own jails and prisons. Americans who claim to be worried about allowing alleged terrorists into their own backyards would be well advised to recognize what's already happening in their own backyards. The U.S. prison system as it now exists makes even less sense than the prison camp at Guantanamo. And unlike Guantanamo, no matter what we may wish, it won't be contained, ignored, or walled off forever.

But there's the rub: We already have a prison problem, and it's already in our backyards. That's what Sen. James Webb, D-Va., wants us to understand as he launches an ambitious new effort to reform U.S. prisons nationwide. It's not quite as dramatic as the prospect of Abu Zubaydah escaping from the Supermax prison in Colorado and rampaging through the Rockies, but the U.S. prison crisis gets worse every year, and nobody seems to mind. Webb has decided to try to reignite the subject of prison reform, because he's convinced that when it comes to the prison problem, Americans need only know how to count.

Here are the facts about America's prisons, according to Webb:

The United States, with 5 percent of the world's population, houses nearly 25 percent of the world's prisoners. As Webb has explained it, "Either we're the most evil people on earth, or we're doing something wrong." We incarcerate 756 inmates per 100,000 residents, nearly five times the world average. At this point, approximately one in every 31 adults in the United States is in prison, jail, or on supervised release. Local, state, and federal spending on corrections now amounts to about $70 billion per year and has increased 40 percent over the past 20 years.

Webb has no problem locking up the serious baddies. In fact, he wants to reform the justice system in part so that we can incapacitate the worst of the worst. But Webb wants us to recognize that warehousing the nation's mentally ill and drug addicts in crowded correctional facilities tends to create a mass of meaner, more violent, less employable people at the exits. And unlike Guantanamo, there are always going to be exits.

The Justice Department estimates that 16 percent of the adult inmates in American prisons—more than 350,000 of those incarcerated—suffer from mental illness; the percentage among juveniles is even higher. And 2007 Justice statistics showed that nearly 60 percent of the state prisoners serving time for a drug offense had no history of violence and four out of five drug arrests were for drug possession, not sales. Webb also reminds us that while drug use varies little by ethnic group in the United States, African-Americans—estimated at 14 percent of regular drug users—make up 56 percent of those in state prison for drug crimes. We know all of this. The question is how long we want to avoid dealing with it.

Why does the senator from one of the country's most rabid lock-'em-up states believe that with two wars raging, an economy collapsing, and America's Next Top Model beckoning seductively, Americans are truly ready to grapple with his new legislation—the National Criminal Justice Commission Act of 2009—which establishes a blue-ribbon commission to review the nation's entire prison system?

Fear-based policies only get you so far, and when it comes to drugs and prisons, it's time to start thinking about reality. Webb says he looks forward to the challenge of communicating the problem to Americans and working together to solve it. He suspects that if Americans actually have the reality-based conversation about our disastrous prison policies, we'll understand that the trends all move in very dangerous directions: We lock up more people for less violent crime at ever greater expense, ultimately breeding more dangerous criminals and ignoring the worst.

The Guantanamo problem we've finally started to grapple with in a pragmatic, rather than symbolic, way—it's a dangerous place with some dangerous people—is a mere speck in the eye of America's larger prison program. An AP story last week described a small Montana town that was more than willing to take all of the Guantanamo prisoners and incarcerate them because, ultimately, a jail is a jail and prisoners are prisoners. If we are so worried about locking up a few terrorists for life in maximum-security U.S. jails, shouldn't we be giving at least some thought to the folks already there? As Dennis Jett observed recently in the Miami Herald, "even if everyone at Guantánamo were transferred to a U.S. prison it would amount to an increase of less than one hundredth of one percent in the total number incarcerated in this country."

Compared with the powder keg of our domestic prison system, Guantanamo actually starts to look pretty benign. And if we are going to have a huge national panic attack about detaining dangerous individuals after 9/11, let's be honest that the dangers of a handful of Guantanamo prisoners "rejoining the battlefield" or escaping from maximum-security prisons is far more remote than the crisis now festering in our own jails and prisons. Americans who claim to be worried about allowing alleged terrorists into their own backyards would be well advised to recognize what's already happening in their own backyards. The U.S. prison system as it now exists makes even less sense than the prison camp at Guantanamo. And unlike Guantanamo, no matter what we may wish, it won't be contained, ignored, or walled off forever.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)